The cancer drug was ready. But 800 approval steps stood in its way.

That wasn’t a science problem. It was a structure problem.

At Bayer, one of the world’s oldest life sciences companies, bureaucracy had quietly strangled speed. Teams trying to save lives were trapped in spreadsheets, risk reviews, and rituals of approval. What should have taken days dragged into quarters. The cost? Time. Energy. And, sometimes, outcomes for patients and customers who couldn’t afford to wait.

The people closest to the work — scientists, agronomists, and sales reps — carried urgency and ideas, but their voices were muffled by the weight of approvals. Each extra layer didn’t just slow outcomes; it drained the energy and creativity needed to sustain innovation.

And Bayer wasn’t alone.

In August 2025, MIT issued a stark report: 95% of enterprise GenAI pilots were failing to deliver business value. Not because the models were flawed — but because the organizations were. Leaders blamed tech. But the truth lay elsewhere: in misalignment, fractured autonomy, and the slow suffocation of accountability.

MIT’s NANDA initiative found the root cause: structural failure. Strategy wasn’t aligned. Teams weren’t empowered. Accountability had thinned into rituals of reporting.

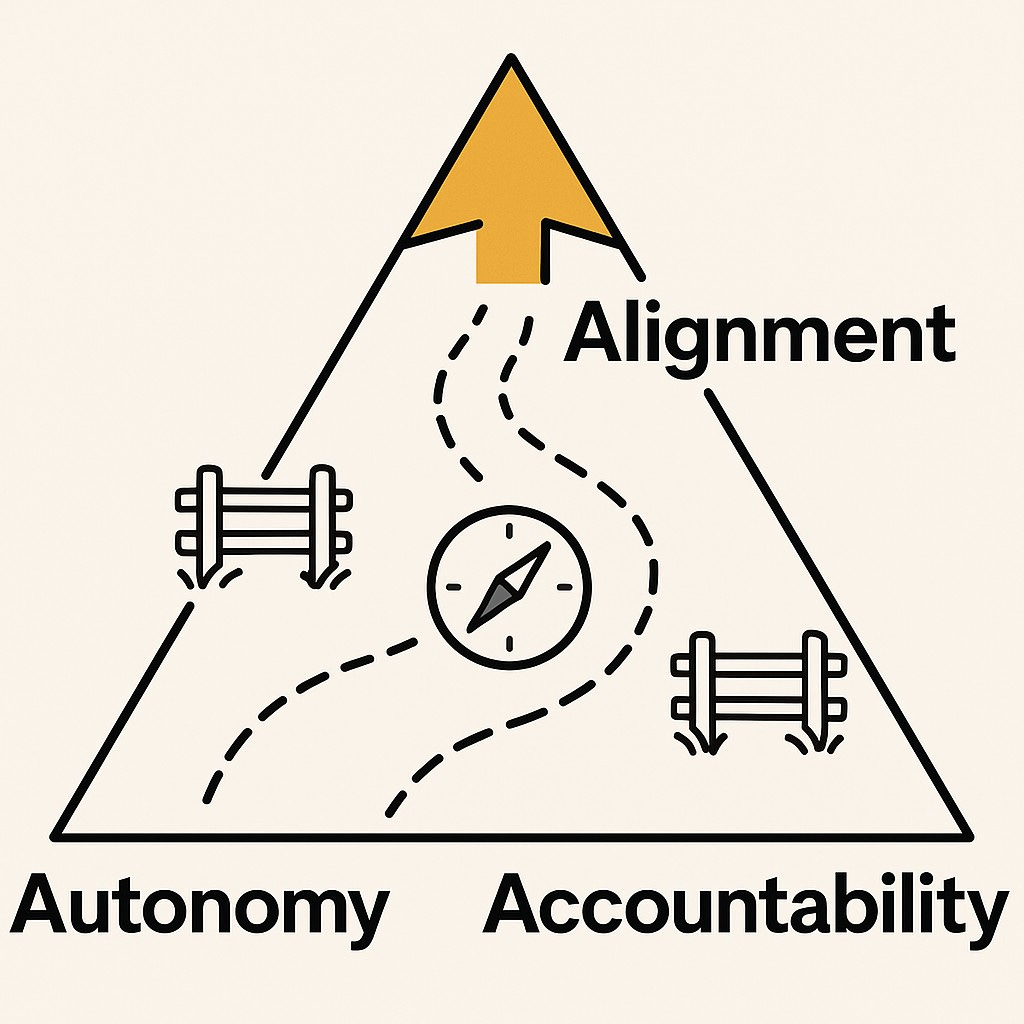

To put it simply: AI wasn’t falling short — organizations were. The triangle was breaking. Alignment. Autonomy. Accountability. And the cracks that MIT spotlighted are the same ones Bayer struggled to repair.

Bayer had learned this the hard way. Crop scientists were bottlenecked by headquarters. Internally, they joked about needing a machete to navigate the company’s org chart.

This wasn’t a tech story.

It was a survival story.

The Triangle and the Balance of Freedom

Every organization runs on a fragile geometry: Alignment, Autonomy, Accountability. Together they create motion — the clarity of direction, the freedom to act, and the responsibility to deliver. Tip the balance, and the triangle bends into dysfunction.

Push alignment too hard and it curdles into rigidity. Grant autonomy without anchor and you invite drift. Lean too far into accountability and you get dashboards glowing green while everyone in the room knows the truth is bleeding red.

This was the geometry Bayer struggled with. Years of layering and approvals had left alignment stranded at the top. Frontline teams — scientists, agronomists, sales reps — were working hard, but their autonomy was fragmented, detached from a coherent whole. What reached them often felt less like a compass and more like the old childhood game of “telephone”: a message that starts crisp but, by the time it passes through a dozen layers of management, is mangled beyond recognition.

Bill Anderson, Bayer CEO, “Bureaucracy has put Bayer in a stranglehold. Our internal rules for employees span 1,362 pages. We have excellent people… trapped in 12 levels of hierarchy, which puts unnecessary distance between our teams, our customers, and our products.”

Jeff Smith, former CIO at IBM, measured this kind of heaviness as “bureaucracy mass index (BMI)” — the organizational equivalent of excess weight that slows every move. Bayer never used that phrase, but the analogy fit. Decisions that should have taken hours dragged into weeks. An oncology team found themselves buried under hundreds of approval steps before a cancer drug could launch. Crop Science sales squads described tailoring customer programs only to have them bounce through endless headquarters reviews.

By opening decision-making, Dynamic Shared Ownership (DSO) didn’t just cut steps — it widened the circle of voices shaping outcomes. Scientists, agronomists, and reps who once felt stifled were suddenly able to see their judgment matter. The effect wasn’t only faster results; it restored pride and energy, creating a more sustainable rhythm of work.

The paradox Bayer confronted was simple to state and maddeningly hard to solve: people crave freedom, yet they also need direction.

Flattening hierarchies gave teams more autonomy — but without a strong compass, that freedom could scatter into chaos. The leadership team knew they couldn’t just push decisions downward; they had to make sure clarity traveled downward too. And in an organization of nearly 100,000 people, clarity rarely survives the journey.

That’s why Anderson and his leadership circle bet on Dynamic Shared Ownership. Instead of pushing strategy through a dozen layers, DSO tethered teams directly to outcomes. Thousands of small, cross-functional “squads” were given ownership over a product, a customer segment, or a local market. They weren’t waiting on a manager’s green light; they were free to make decisions as long as those decisions aligned with Bayer’s mission: Health for all, Hunger for none.

The oncology launch became a proof point. The squad asked a single question: “Will this help patients faster?” By stripping out unnecessary steps, they moved at record speed. In Crop Science, field reps who once waited weeks for headquarters approval were tailoring solutions with local retailers in hours. Farmers noticed. Patients noticed. And so did Bayer’s weary employees — suddenly they had both freedom and purpose.

But DSO was not a license for anarchy. Autonomy came inside guardrails: quarterly 90-day planning cycles, shared mission outcomes, and a cultural reset that shifted leaders from bosses to coaches. Teams could choose their route, but the mountain they were climbing was non-negotiable.

In other words, Bayer was rediscovering what many organizations forget:

Alignment gives autonomy its aim; Autonomy gives alignment its life.

What Leaders Face

Flattening an organization doesn’t erase the hard choices. If anything, it sharpens them. Bayer’s leaders quickly discovered that autonomy without alignment is just noise, and alignment without autonomy is dead weight. The challenge was not declaring a new model; it was living with the tensions that model created.

First dilemma: coherence without micromanagement. With hundreds of squads now self-organizing, how do you keep them rowing in roughly the same direction? Bayer’s answer was to replace annual planning with 90-day cycles. Every quarter, teams set outcomes, shared them across the network, and adjusted based on feedback. The cycles created rhythm without rigidity — a cadence that synchronized without suffocating.

Second dilemma: autonomy without drift. When you tell 100,000 employees they now “own the work,” some will sprint in wildly different directions. Bayer countered this by redefining leadership roles:

Visionaries co-created missions with teams.

Architects helped design how value got created.

Catalysts connected squads so learning could spread laterally.

Coaches stood beside teams in their 90-day cycles, offering feedback.

One division head summed up the shift bluntly: “Be proud that you weren’t needed.” In other words, leaders measured success by how well their teams could act without them.

Third dilemma: sustaining clarity across layers. Even in a flattened company, the gravitational pull of bureaucracy doesn’t vanish overnight. To reinforce the new model, Bayer codified two mindset shifts — from preservation to possibility, and from conformity to self-authorship. Employees weren’t just asked to work differently; they were invited to think differently.

These shifts also broadened the circle of leadership. Decisions weren’t the privilege of a few; they became a shared capacity across squads. For many employees, this wasn’t just about new processes — it was about dignity, ownership, and the chance to contribute fully. The new rhythm wasn’t only adaptive; it was sustainable, building resilience for the long haul.

It mattered. Crop Science squads were making customer decisions in hours instead of weeks. An Italian team spotted a patient problem and 3D-printed a €6 device in days — something that might have taken years under the old hierarchy. These weren’t isolated wins; they were proof that leadership’s role had shifted from controlling the work to creating the conditions for work to flourish.

Practices That Work

The real test of any operating model isn’t in the design slides — it’s in the day-to-day grit of how people make decisions. At Bayer, a few practices began to separate talk from traction:

Clarity at the source. Strategy was embodied, not laminated. The oncology team’s mantra — “Will this help patients faster?” — mattered more than a dozen PowerPoints.

Guardrails, not guard towers. Quarterly cycles kept squads moving fast but safe.

Trust as glue. Leadership involved employee reps and unions from the outset, even during layoffs. Guarantees and retraining built confidence that DSO wasn’t slash-and-burn.

Culture as carrier. Rituals (peer recognition, storytelling, symbols) reinforced alignment better than policies.

These weren’t perfect solutions. They were imperfect experiments, adapted every quarter. But they created motion — exactly what Bayer needed after years of bureaucratic paralysis.

What emerged was more than efficiency. Teams reported a renewed sense of agency and creativity — a reminder that when systems invite broader voices, people thrive. These practices weren’t just about fixing today’s problems; they laid the groundwork for a healthier, more sustainable organization.

And Bayer’s hard-earned lessons offer a bridge to the present debate. Because what they were wrestling with in 2023 and 2024 is the same fault line MIT exposed in 2025.

AI as Magnifier

The company’s NANDA initiative found that 95% of enterprise GenAI pilots stall, not because models underperform, but because structures do.

The study’s details are telling. Over half of AI budgets flowed into sales and marketing, yet the biggest ROI came from back-office automation. That’s misalignment in budget form.

MIT found that companies building AI tools internally succeeded only a third of the time. Purchased solutions, deployed through partnerships, worked twice as often. Autonomy in isolation turned into waste; autonomy in ecosystems created results.

Shadow AI was everywhere — employees already acting autonomously with unsanctioned tools. The accountability question loomed: harness it, or drive it underground?

MIT’s researchers warned the next phase, agentic AI, will magnify whatever structures it enters. A healthy triangle will scale agility; a broken triangle will scale dysfunction.

Dashboards won’t save us. As argued in Next Metrics, signals too often calcify into targets, then threats: “everything green, nothing true.” Add AI and those dashboards don’t get more honest; they just glow brighter. The fix isn’t more data points. It’s a different instrument: a compass. Leaders must sense capability, not just score output.

AI won’t fix your triangle. It will break it faster. And just as Bayer discovered when it rewired decision-making, the lessons of structure and culture shape how any new tool delivers impact. This isn’t just an analyst’s warning — it’s a leadership story still unfolding.

It’s also a human story. When shadow AI surfaced, it wasn’t rebellion for its own sake — it was employees trying to solve problems faster. The challenge for leaders is not only to manage risk, but to channel that creativity inclusively and responsibly, turning experimentation into sustainable progress.

Takeaway: Fix the Triangle Before You Code the Future

If you're betting on AI to transform your business, start here: fix the triangle first.

Because no model — no matter how powerful — can compensate for broken structure. If alignment drifts, autonomy scatters, and accountability fades, your GenAI initiative will follow the same path as so many before it: nowhere.

Bayer didn’t just survive by deploying new tech. It changed how decisions were made. It rewired leadership. It built trust into the system. And it gave autonomy real direction.

This is the hard part. But it’s also the part only you — the leader — can do.

AI won’t fix your triangle.

But you can.

And when you do, the payoff is larger than performance. It’s an organization where people can contribute fully, adapt responsibly, and thrive together — a triangle strong enough to sustain progress in the age of AI.